This review contains a few excerpts from the book but doesn't spoil any surprises.

Featuring just five short pieces, Him With His Foot In His Mouth might be an ideal introduction for those who have never read anything by Saul Bellow. The collection showcases his unique voice and style, while familiar readers can find some interesting new perspectives on the usual themes.

Featuring just five short pieces, Him With His Foot In His Mouth might be an ideal introduction for those who have never read anything by Saul Bellow. The collection showcases his unique voice and style, while familiar readers can find some interesting new perspectives on the usual themes.The longest story in the collection, for example, is called 'What Kind Of Day Did You Have?'. It's underscored by Bellow's trademark examination of what it means to live in a mass society more organised than its individual members, among the rubble of grand ideas and failed dreams. At the centre of the piece is Victor Wulpy, a mouthpiece for Bellow's various anthropolitical musings, trying 'to pole his way upon a walking stick against the human tides of airports'.

This single image is a nice example of Bellow's style. As a general observation it's both striking and familiar, but it conveys something about the character too — in this case, a celebrated intellectual moving through and against the crowds. The twist in the telling of this story is that Victor is mostly portrayed as seen through the eyes of Katrina, the woman he has left his wife to be with.

The story isn't told from Katrina's perspective as such. Instead, Bellow writes in a free indirect style and creates a more socialised narrative, rather than relying completely on the illusion of miraculous telepathy that fiction writers often employ. This basically amounts to some breathtaking use of the second-person:

The story isn't told from Katrina's perspective as such. Instead, Bellow writes in a free indirect style and creates a more socialised narrative, rather than relying completely on the illusion of miraculous telepathy that fiction writers often employ. This basically amounts to some breathtaking use of the second-person:The jet engines sucked and snarled up the frozen air; the huge plane lifted; the gray ground skidded away and you rose past hangars, over factories, ponds, bungalows, football fields, the stitched incisions of railroad tracks curving through the snow.The technique encourages us to empathise with the nearly selfless Katrina. Wulpy is, in some ways, a stock Bellow character but with all the neuroses trimmed away or at least hidden, due to perspective. This makes him formidable indeed and Katrina is left to grovel and apologise on his behalf. He comes across, therefore, as a figure of intimidating intellect, brought down to a common, sympathetic level only by age. His life is, at one point, described as 'the crazy intensity that could not be shared'; through Katrina, Bellow does his very best to convey the heat of that intensity.

All the other stories in the collection are told in the first-person, something Bellow is very accomplished at. While his style is not exactly what one might describe as "stream-of-consciousness", these rambling, roundabout forms do approximate something like memory, or at least the shabbiness of human recollection.

The title piece has at its heart an amusing figure — perhaps a less intellectual version of one of Bellow's more famous characters, Moses Herzog. The story takes the form of the awkward first draft of a long written apology to a woman the character knew only briefly many years before.

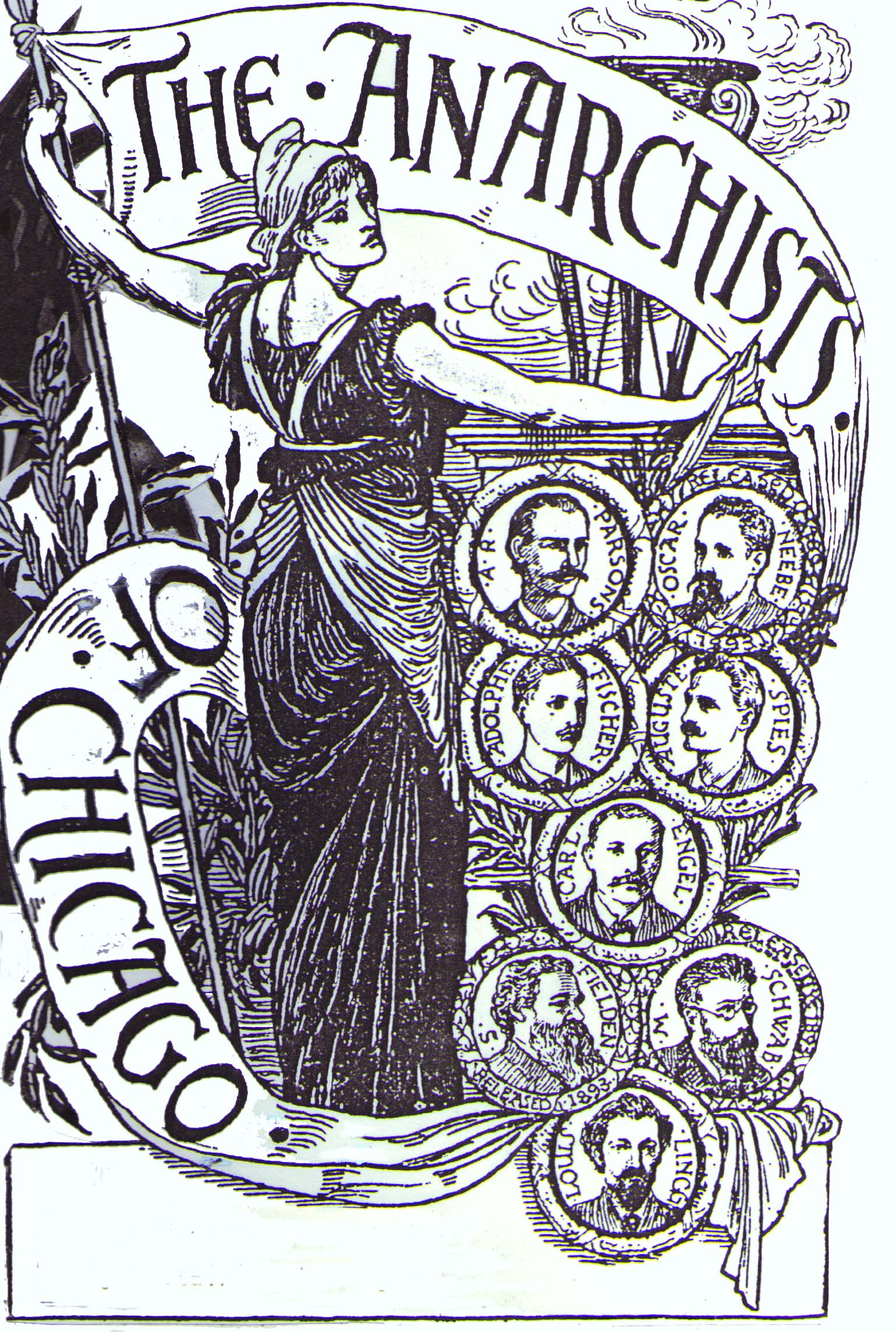

'Zetland: By A Character Witness' is the shortest piece and sketches a character who for once seems to believe in the idea of fidelity — a rarity for Bellow's male characters, though this of course might well be down to omissions on the narrator's part. Romantic as well are the nostalgic glimpses of 30s America with its 'Chicago anarchists and Wobblies' gathering in Humboldt Park, while Zet and his wife settle in together among '[c]rusts, butts, coffee grounds, dishes of dog food, books, journals, music stands, odors of Macedonian cookery (mutton, yoghurt, lemon, rice), and white Chilean wine in bulbous bottles'.

Bellow's narrator seems enamoured of this chaotic life at least, and one might perhaps dare to suggest that Bellow himself had a certain fondness for it. This seems to be the one piece where the past isn't an embarassment; there's a sense of nostalgia for a time before politics itself got 'sucked and snarled' into a jet engine of moneyed schemes. The queasy excitement of youth, young love, and living in the moment is captured beautifully:

From so much sweetness, this chocolate life, nerves glowing too hotly, came pangs of anxiety. In its own way the anxiety was also delicious, he said [...] ecstasy, sensuous and sick.In the middle of this beautiful chaos and its tender worries, Zetland is caught up in his own intellectual pursuits and the story allows for some occasional insights:

There is probably no way for human beings to avoid playacting, Zet said. As long as you know where the soul is, there is no harm in being Socrates. It is when the soul can't be located that the play of being someone turns desperate.The other thing that we human beings haven't yet worked out how to avoid of course is death. Beginning with a musing on death, 'A Silver Dish' has possibly the blackest humour of the lot. The narrator remembers his father and recalls an incident in which they wrestle each other desperately for a silver dish the father wants to steal while its owner is upstairs, fetching them a small loan of cash.

Taken together then, these stories might be said to constitute a shambling search for something like the "human soul" — and even if we're only a little wiser by the end, the resultant comedy makes accompanying Bellow on his quest worthwhile. If there is an "answer" it might be provided by the final piece, 'Cousins', in which the narrator gives an account of various of his relations, all of whom seem strange to him, despite their having been in his life for nearly as long as he can remember.

The central implication in this otherwise arbitrary collection might be that we can only find ourselves in our relations with other people but that modern city life cuts us off from one another just as easily as it masses us together. With the exception of the nostalgic 'Zetland', these urbane pieces describe social relations that have become all negotiation and compromise. We all end up 'playacting' when, underneath our sheep's clothing, we've become 'desperate' and very much lone wolves... But now I'm putting words in Bellow's mouth. If you're interested in these kinds of notions though, this book's well worth a look. Modern science may not be able to locate the "soul" but, as to its approximate whereabouts, Bellow provides plenty of spirited guesses.

No comments:

Post a Comment